-

Posts

36,378 -

Joined

-

Last visited

About bluewave

Profile Information

-

Gender

Male

-

Location:

KHVN

Recent Profile Visitors

61,325 profile views

-

2026-2027 El Nino

bluewave replied to Stormchaserchuck1's topic in Weather Forecasting and Discussion

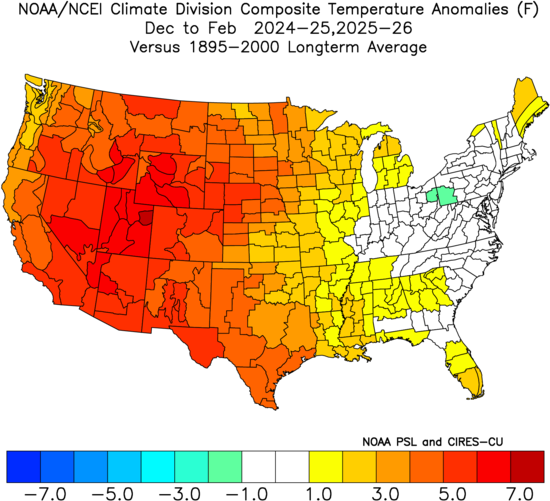

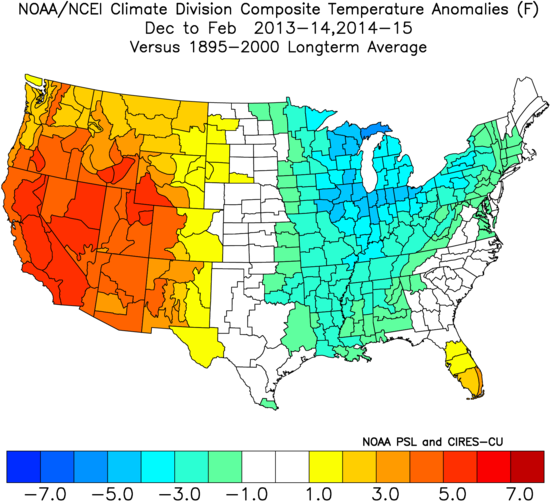

It’s interesting how we got a much warmer and less snowy version of 2013-2014 and the 2014-2015 the last two winters. This is what I was getting at in my discussions over the last few years. The cold pool and polar vortex over North America was much smaller during the last few winters with a more expansive and stronger 500 mb ridge. So Boston couldn’t challenge their snowiest winter in 2014-2015 with the February 2015 cold and the Great Lakes couldn’t approach 2013-2014 record snow and cold. The last few winters were a warmer and less snowy reflection due to the big global temperature jump which occurred with the 2015-2016 super El Niño. -

2026-2027 El Nino

bluewave replied to Stormchaserchuck1's topic in Weather Forecasting and Discussion

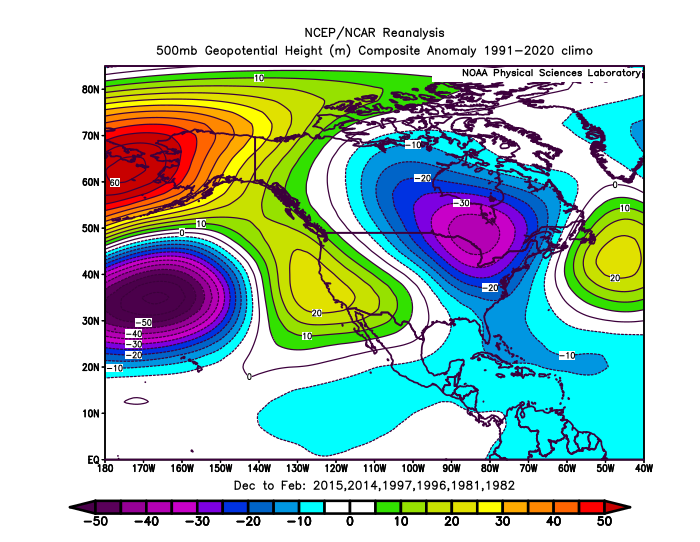

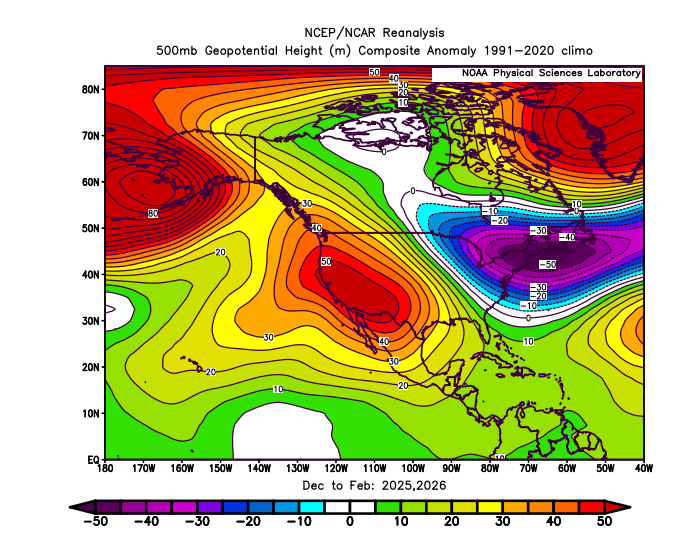

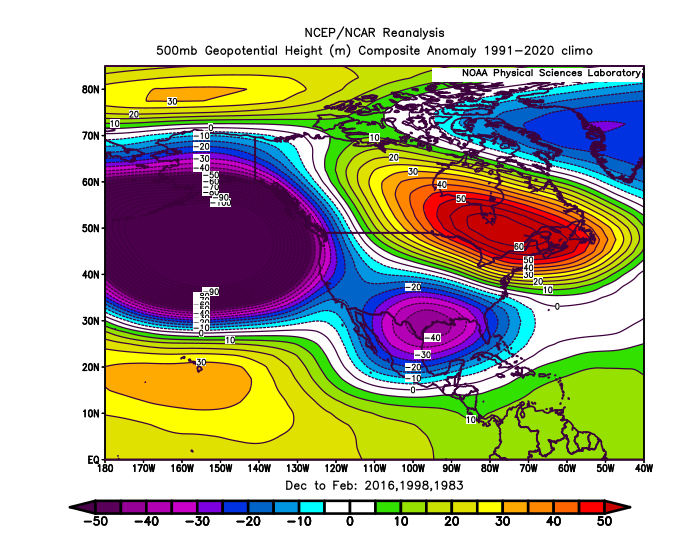

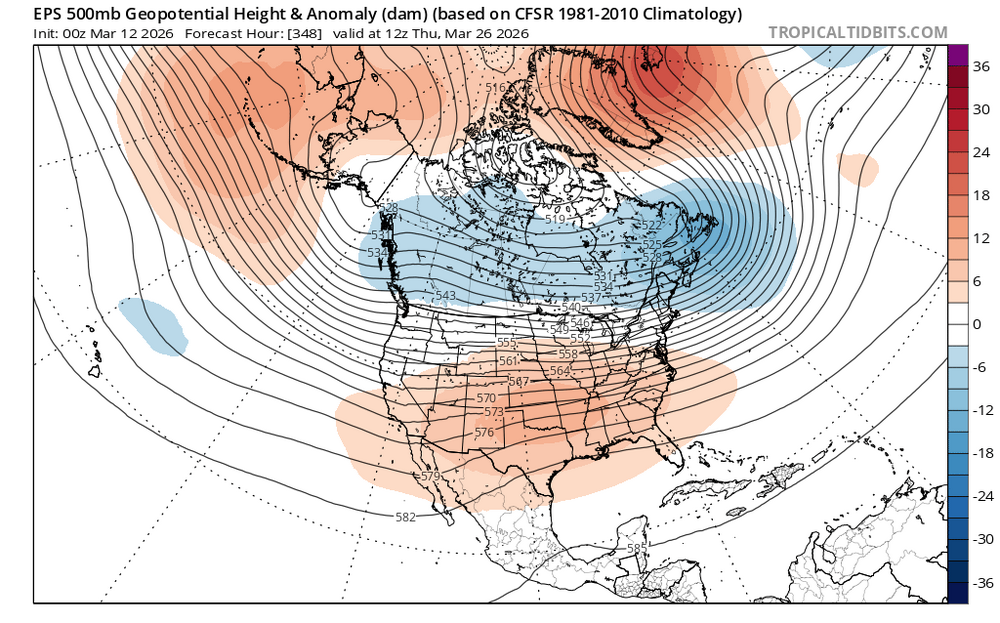

I can see why the models are going so strong with the El Niño next winter. The last two winters followed the North Pacific strong El Niño precursor pattern. This two winter regime featured a strong -WPO in the Bering Sea and a ridge over the Western North America. But we will need to watch the El Niño development going forward to see if the El Niño is as robust as 2015-2016, 1997-1998, and 1982-1983. Probably need to get through the spring forecast barrier period before we have an idea about next winter. If the previous multiyear composite works out, then the ridge next winter will be centered just north of the Great Lakes into the Northeast. This progression below isn’t a forecast yet, but something to watch for if the El Niño becomes as strong as model forecasts. Plus the sample size only consists of 3 multiyear periods since 1981. 2024-2025 and 2025-2026 winter 500 mb composite 2014-2015, 2013-2014, 1996-1997, 1995-1996, 1981-1982, and 1980-1981 composites Roll forward to the 2015-2016, 1997-1998, and 1982-1983 winters -

Yeah, I agree. It was significantly deeper than the Blizzard of 1888. Had March 1993 taken a benchmark track instead, then we would have had a 40”+ jackpot with 80-100 mph gusts somewhere in the OKX forecast zones and drifts approaching 6-10 feet high in spots. https://www.weather.gov/media/ilm/Overview_Kocin_Schumacher_Morales_Uccelini.pdf

-

That was the last time many locations near the coast had a 10”+ snowstorm after February with the exception of our local snow capital and nearby spots back in 2018. Maximum 2-Day Total Snowfall for NEWARK LIBERTY INTL AP, NJ After February Click column heading to sort ascending, click again to sort descending. 18.2 1956-03-19 0 15.8 1915-04-04 0 - 15.8 1915-04-03 0 14.8 1958-03-21 0 13.9 1960-03-04 0 12.8 1982-04-07 0 - 12.8 1982-04-06 0 12.7 1993-03-14 0 - 12.7 1956-03-20 0 12.5 1960-03-03 0 12.1 1941-03-09 0 12.0 1941-03-08 0 - 12.0 1924-04-02 0 - 12.0 1924-04-01 0 - 12.0 1852-03-18 0 - 12.0 1852-03-17 0 11.9 1993-03-13 0 11.5 1896-03-16 0 11.0 1867-03-18 0 - 11.0 1867-03-17 0 10.5 1851-03-08 0 Maximum 2-Day Total Snowfall for ISLIP-LI MACARTHUR AP, NY After February Click column heading to sort ascending, click again to sort descending. 18.4 2018-03-22 0 17.0 1967-03-22 0 16.0 1982-04-07 0 - 16.0 1982-04-06 0 15.0 1967-03-23 0 14.9 2018-03-21 0 13.5 2009-03-02 0

-

Some of the strongest backdoor cold fronts on record in the Northeast during the spring have occurred following record warmth. https://www.wunderground.com/history/daily/us/ma/east-boston/KBOS/date/2002-4-17 PM 93 °F 51 °F 24 % W 18 mph 23 mph 29.83 in 0.0 in Mostly Cloudy 4:54 PM 93 °F 49 °F 22 % W 17 mph 26 mph 29.82 in 0.0 in Partly Cloudy 5:54 PM 91 °F 49 °F 23 % W 14 mph 0 mph 29.82 in 0.0 in Mostly Cloudy 6:32 PM 66 °F 50 °F 56 % NNE 26 mph 33 mph 29.87 in 0.0 in Mostly Cloudy / Windy 6:54 PM 59 °F 50 °F 72 % NNE 25 mph 35 mph 29.91 in 0.0 in Cloudy / Windy 7:54 PM 55 °F 49 °F 80 % ENE 7 mph 0 mph 29.95 in 0.0 in Mostly Cloudy 8:54 PM 55 °F 50 °F 83 % N 8 mph 0 mph 29.96 in 0.0 in Partly

-

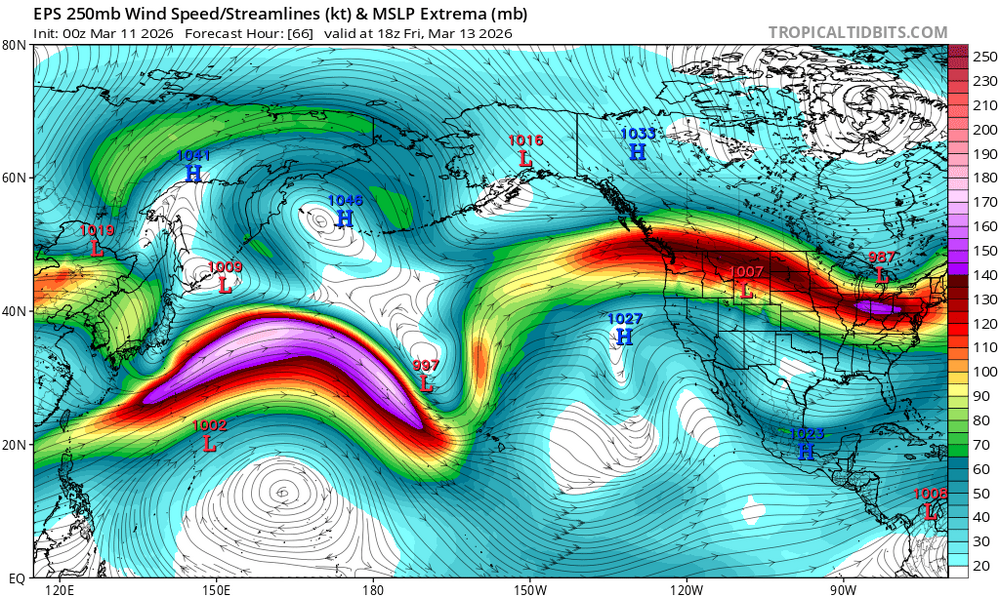

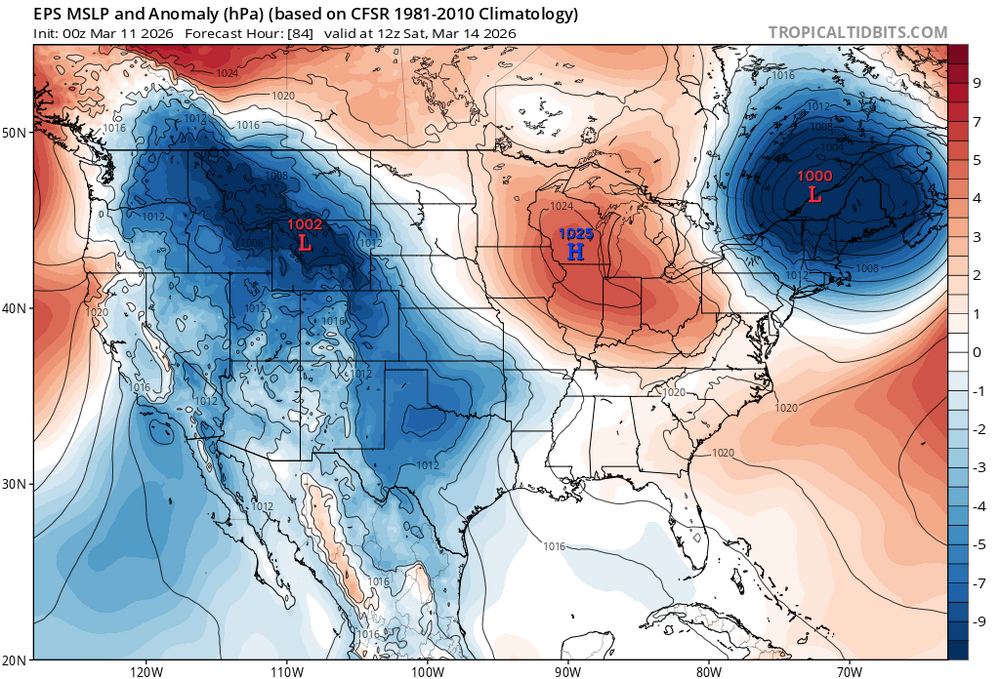

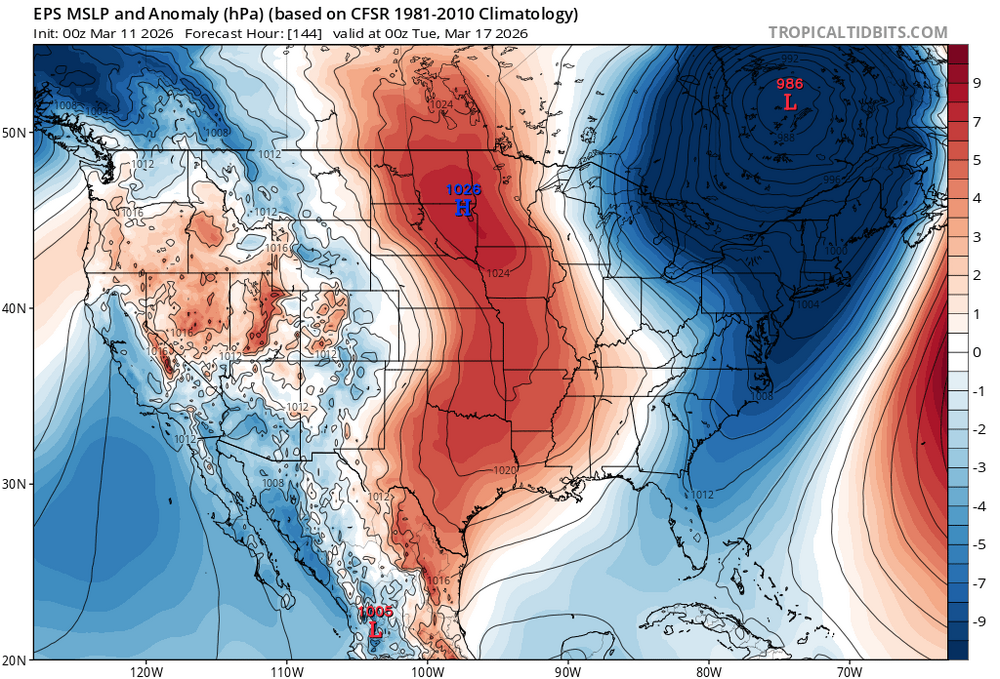

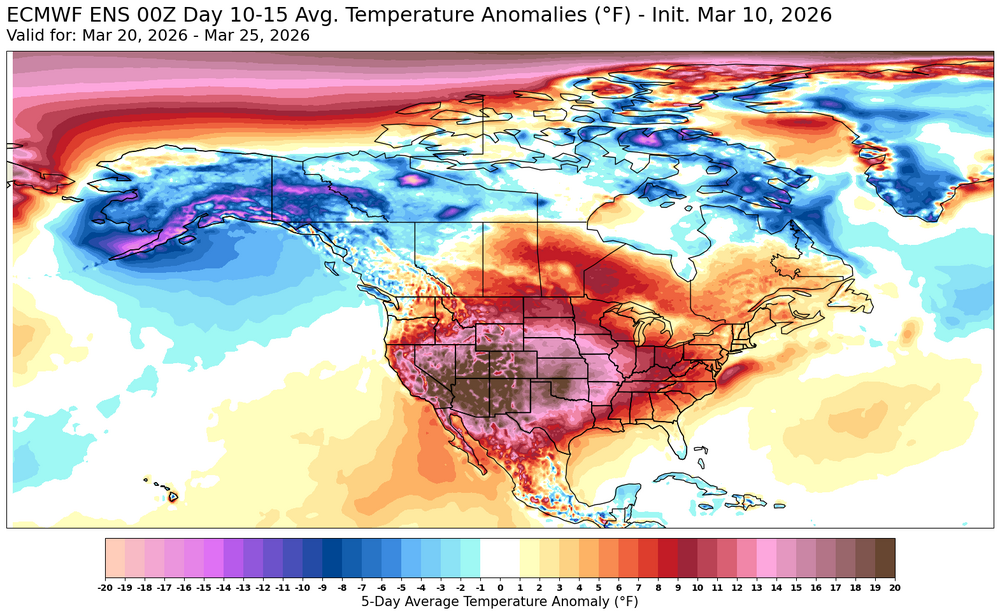

We’ll see if the long range EPS is correct about the backdoor potential for later in the month as it has a return to some Greenland blocking.

-

Parts of Florida also experienced some snow following a record 80° day back in January. Climatological Data for Pensacola Area, FL (ThreadEx) - January 2026 Click column heading to sort ascending, click again to sort descending. 2026-01-01 68 41 54.5 1.1 10 0 0.00 0.0 0 2026-01-02 71 51 61.0 7.7 4 0 0.03 0.0 0 2026-01-03 74 58 66.0 12.8 0 1 1.47 0.0 0 2026-01-04 65 51 58.0 4.8 7 0 0.00 0.0 0 2026-01-05 65 50 57.5 4.4 7 0 0.00 0.0 0 2026-01-06 76 60 68.0 15.0 0 3 0.00 0.0 0 2026-01-07 77 64 70.5 17.5 0 6 0.00 0.0 0 2026-01-08 70 62 66.0 13.1 0 1 T 0.0 0 2026-01-09 75 65 70.0 17.1 0 5 0.00 0.0 0 2026-01-10 80 62 71.0 18.1 0 6 0.19 0.0 0 2026-01-11 62 43 52.5 -0.4 12 0 0.00 0.0 0 2026-01-12 52 36 44.0 -8.8 21 0 0.00 0.0 0 2026-01-13 58 31 44.5 -8.3 20 0 0.00 0.0 0 2026-01-14 61 45 53.0 0.2 12 0 0.10 0.0 0 2026-01-15 50 32 41.0 -11.8 24 0 0.00 0.0 0 2026-01-16 65 30 47.5 -5.4 17 0 0.00 0.0 0 2026-01-17 59 44 51.5 -1.4 13 0 0.03 0.0 0 2026-01-18 49 32 40.5 -12.4 24 0 0.10 T RECORD EVENT REPORT NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE MOBILE AL 145 AM CST SUN JAN 11 2026 ...RECORD HIGH TEMPERATURE SET AT PENSACOLA... A RECORD HIGH TEMPERATURE OF 80 DEGREES WAS SET AT PENSACOLA YESTERDAY. THIS BREAKS THE OLD RECORD OF 79 DEGREES SET IN 1957.

-

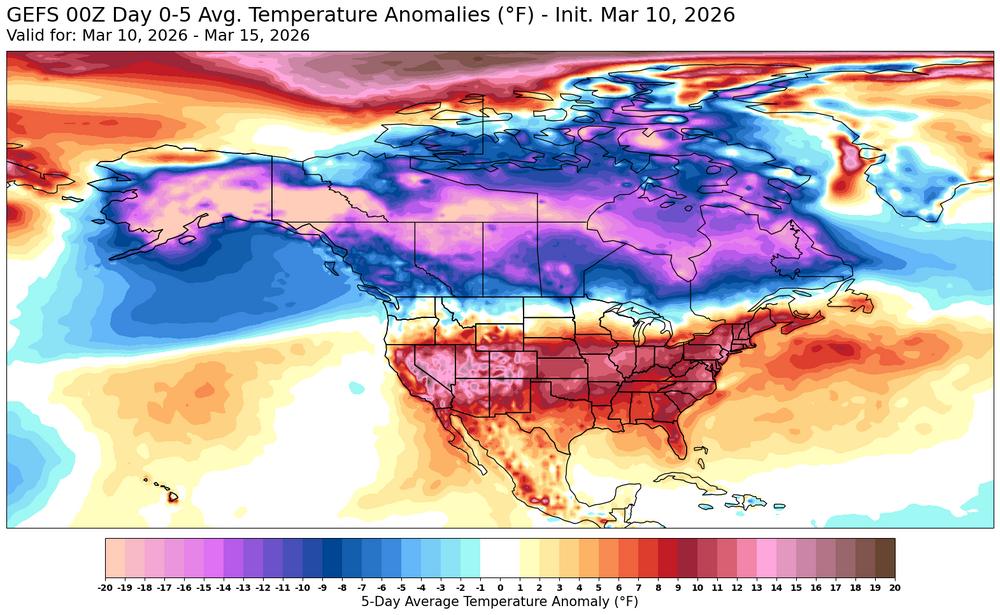

It’s great that we got a one month relaxation of the Northern Stream from late January into late February. But now it’s back as strong as ever. This is the main reason that our significant snowfall chances have diminished after February.

-

The record high of 80° at Central Park was the earliest 80° day on record. First/Last Summary for NY CITY CENTRAL PARK, NY Each section contains date and year of occurrence, value on that date. Click column heading to sort ascending, click again to sort descending. 2026 03-10 (2026) 80 - - - 1990 03-13 (1990) 85 10-14 (1990) 80 214 1945 03-20 (1945) 83 10-19 (1945) 80 212 1921 03-21 (1921) 84 09-30 (1921) 87 192 2021 03-26 (2021) 82 09-18 (2021) 84 175 1998 03-27 (1998) 83 09-27 (1998) 89 183 1989 03-28 (1989) 82 09-23 (1989) 81 178 1977 03-29 (1977) 81 09-19 (1977) 81 173 1985 03-29 (1985) 82 10-15 (1985) 80 199 2025 03-29 (2025) 81 10-07 (2025) 80 191 1917 04-01 (1917) 83 09-20 (1917) 84 171 1978 04-01 (1978) 82 09-21 (1978) 83

-

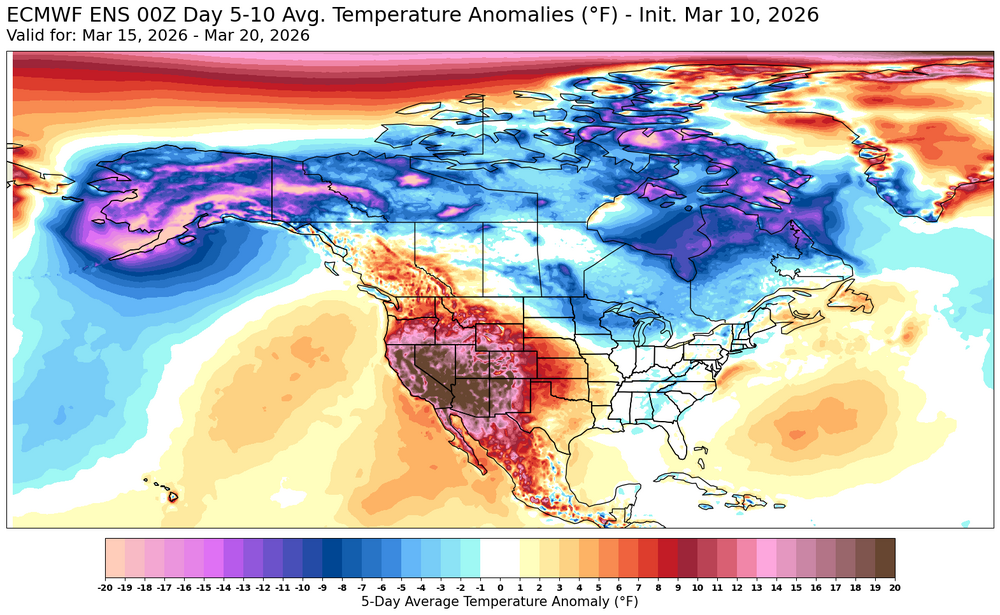

It will be interesting to see if this pattern continues into the summer with pieces of the Western heat coming east from time to time.

-

Many of the big snow piles melted up here. Now large pieces of broken curbs are being exposed that were plowed up under the snow. So we are going to need new curbs and pothole repair since the roads are in very rough shape. Also big piles of mud where the snow was as chunks of lawns were caught up in the plows. Hopefully we can get some more rain this summer as the grass went brown pretty quick last summer with the record heat and lack of rainfall. Reservoirs got recharged a bit this winter as they dropped to low levels here at times since September 2024.

-

How can you debunk statements which were never made in the first place? This was our first winter with benchmark KU events since January 2022. There wasn’t a statement made that we would never see benchmark storm tracks again. What was discussed was how long it would take for them to return and what mechanism would be involved. All it took was one of the earliest November stratospheric warming events related to the -QBO and record low sea ice. But such events aren’t well forecast much in advance. Record Western Pacific SSTs mean frequent MJO 4-7 phases but not always constant. This was our first successful MJO 8 event since January 2022. The NAO has frequently been connecting with the Southeast Ridge but not 100% of the time. In fact, the Southeast Ridge link up back in December with the -NAO worked in our favor with the strong -WPO to prevent suppression and deliver a snowy clipper. Record warm ocean temps mean the Southeast ridge has been dominant but intervals when it relaxes have occurred from time to time. Fast flow is an increasing feature as the planet warms. But we saw the first relaxation of this pattern for the blizzard in late February for just long enough for all the pieces to come together in years. Snowy Clippers were very infrequent prior to December and we finally got two great ones after a long hiatus. In reality what we have experienced has been a shift to all or nothing snowfall seasons since the 1990s. So our winters either swing for fences like this winter and and get a bunch of home runs or we strike out like the prior 3 winters. The sense of balance like we used to have with frequent 18-29”snowfall seasons prior to the 1990s has been lacking. So now it’s mostly under 20” or even 15” seasons and over 30”. The challenge with this type of regieme is that we need some exotic device to get the great snowfall outcomes like this winter with one of the earliest SSW in 75 years. We have been doing better than a place like State College which hasn’t had a great Miller A east of the APPS track in over 20 years. So they have been missing out with all the Great Lakes cutters west of the APPS and benchmark tracks which favor the coast.

-

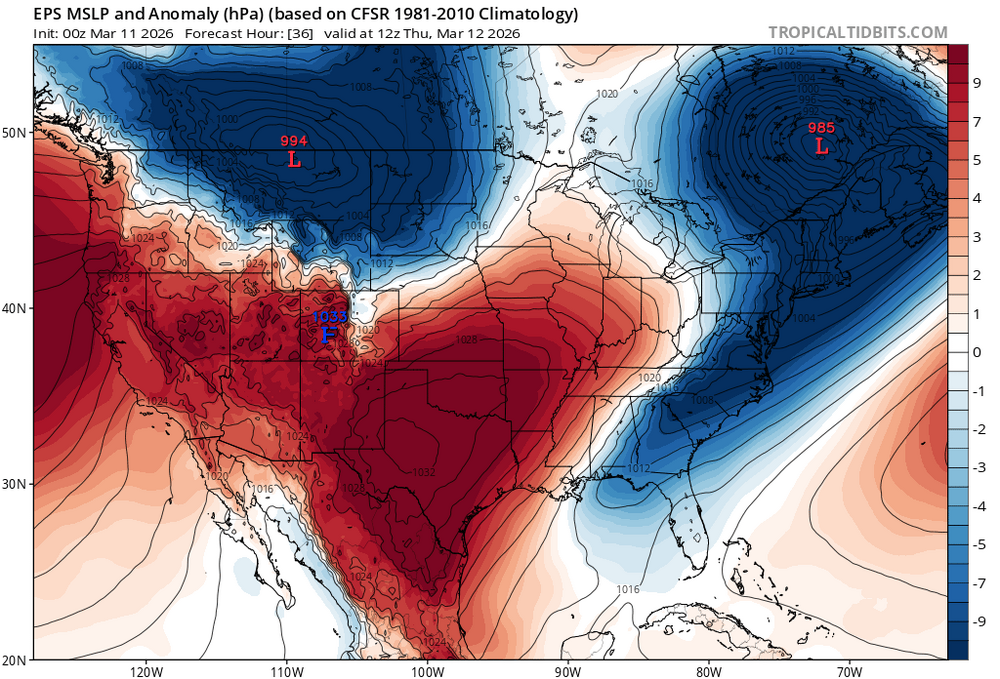

Generally looks like the magnitude of any colder weather during mid to later March will be of a weaker magnitude than the warmth this week.

-

The usual warm spots in NJ have a shot at 4 consecutive days reaching 70°+ which is impressive for so early in the season.