All Activity

- Past hour

-

Spring 2025 Medium/Long Range Discussion

CheeselandSkies replied to Chicago Storm's topic in Lakes/Ohio Valley

Puke. Classic dreaded spring omega block that prevents western troughs from maturing and ejecting properly for events. -

Not for me 30 degree spread common 35 uncommon 3/4 of 10 40 rare I wasn’t starting a point counterpoint anyway

-

Forecast high of 82 today and a low of 37 tonight lol.

-

np ... frankly, I begin to think the PI is less meaningful since ~ 1998 anyway; since, the curve's become less linear and more exponential. That changes the things, because something is happening endemic to these last 2 or 3 decades. It's really like we need to change the narrative to "since pre super NINO 1998"

-

It's just annoying because it blows my pens off my notebook then opens the notebook and blows the pages...that is really annoying when writing. But at least it isn't a cold wind.

-

Spit or swallow?

-

Yeah a few decent gusts down there. Fairly tranquil here so far.

-

2025 Atlantic Hurricane Season

BarryStantonGBP replied to BarryStantonGBP's topic in Tropical Headquarters

Also ignore Joe Bastardi’s babbling on twitter. He’s jumping to conclusions and omitting important information by cropping off graphs he is not seeing the whole picture -

35 mph gusts just ripping pollen bombs everywhere

-

2025 Atlantic Hurricane Season

BarryStantonGBP replied to BarryStantonGBP's topic in Tropical Headquarters

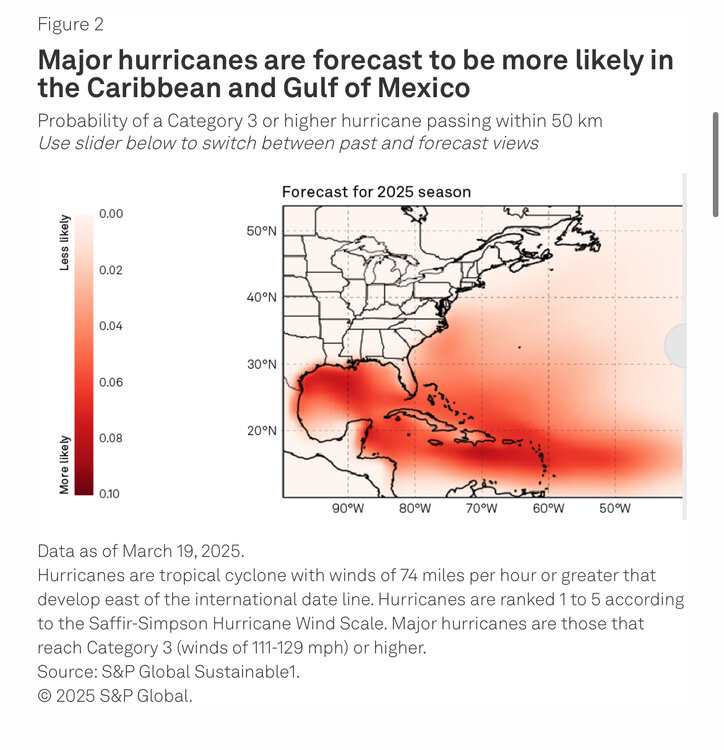

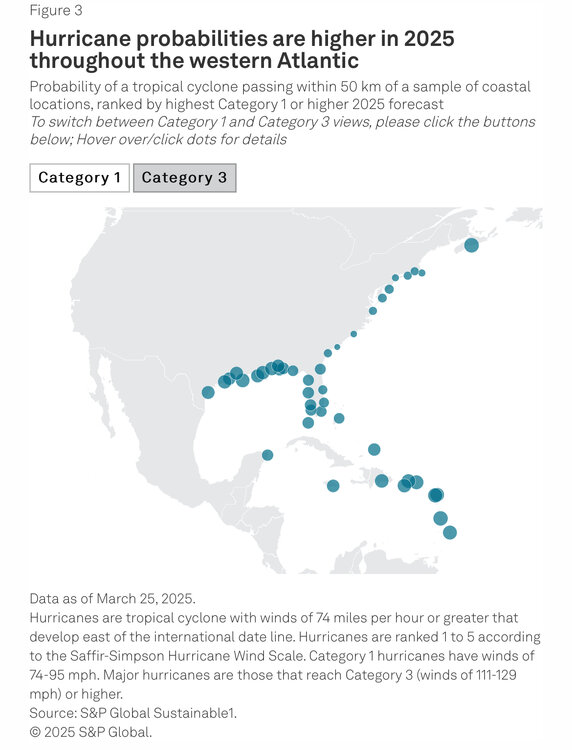

“But decreased landfall expectations!” ”My EURO! My models!” An Elevated 2025 Hurricane Season Forecast for the 2025 Hurricane Season and Retrospective Analysis of the 2024 Forecast Published: April 7, 2025 HIGHLIGHTS The S&P Global Climate Center of Excellence forecasts above-average hurricane activity in the North Atlantic, Caribbean, and the US and Mexican Gulf Coasts for the upcoming 2025 season. Our forecasts include the overall number of hurricanes as well as local probabilities of hurricanes passing nearby. Though lower than 2024, probabilities for impact by a major hurricane on large stretches of US and Caribbean coastlines are still forecast to be 50%-80% above their long-term average values. The driving climate factors in the forecast are El Niño/La Niña and sea surface temperatures in the subtropical North Atlantic. El Niño/La Niña is currently forecast to be close to neutral from July to September, compared to the La Niña state in 2024, while North Atlantic temperatures are forecast to be significantly elevated, though not as high as 2024. In this report we provide details of the forecast, including occurrence probability maps. We also present a retrospective analysis of our forecast for the 2024 season. The 2024 forecast was largely successful, confirming the model’s forecast skill. Authors Timothy Hall | Senior Scientist, S&P Global Climate Center of Excellence Hurricanes: What’s at stake and who could be impacted Powerful tropical cyclones — known as hurricanes in the North Atlantic and typhoons in the Pacific — are among the most deadly and destructive natural disasters on the planet. Understanding them can help protect lives, homes and businesses. The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June through the end of November, and for 2025, the seasonal hurricane model from the S&P Global Climate Center of Excellence forecasts eight hurricanes, with four of them reaching major hurricane status. Hurricane intensity is labeled on a range from Category 1 on the low end up to Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, and major hurricanes are defined as Category 3 and above. The hazard forecast that follows is relevant for many stakeholders, from residents and municipalities to property owners, businesses, and energy production facilities along the US Gulf Coast, US East Coast, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Islands. The information is also relevant to insurers and investors with portfolios located in these regions. We forecast that these stakeholders will have elevated risk to property and infrastructure damage and financial loss in 2025 compared to long-term averages. To put some additional context around what’s at stake here: the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office (NOAA) has tallied 403 weather and climate disasters since 1980 that each resulted in costs of $1 billion or more, with a total cumulative cost of more than $2.9 trillion. Of all those $1 billion-plus weather disasters, tropical cyclones/hurricanes caused the most damage, at over $1.5 trillion total with an average cost of $23 billion per event. Hurricanes also caused the most deaths — more than 7,200 since 1980. Looking ahead: What we’re forecasting for 2025 In most regions of US and Caribbean coastlines, we forecast hurricane occurrence probabilities (passage of a hurricane within 50 km) to be substantially higher than their long-term (1948-2022) mean values. Many sections of US and Caribbean coastline have probability of a hurricane impact (Category 1 and up) approximately 30%-50% higher than the long-term mean (1948-2022), and major hurricane impact (Category 3 and up) 50%-80% higher than the long-term mean. For example, the forecast hurricane impact probability on Corpus Christi, Texas, is 0.078, compared to the 1948-2022 mean of 0.053, an increase of 47%, and major hurricane impact of 0.034 compared to the 1948-2022 mean of 0.019, an increase of 79%. These increased probabilities can be seen in Figures 1 and 2, which show 2025 forecast and 1948-2022 mean maps of impact probability for all hurricanes (Figure 1) and major hurricanes (Figure 2). We show best-estimate probabilities on a mapped sample of coastal locations in Figure 3. Large uncertainty is an inherent feature of seasonal forecasting, and location data available in Figure 3 also lists our lower and upper estimates from our ranges of uncertainty. (There’s a 5% chance the true value falls below the lower estimate or above the upper estimate.) For most locations, however, even the lower estimate forecast sits near or above the 1948-2022 mean, providing confidence in the overall forecast of an above-average 2025 season. Figure 3: Hover over each location to view the probability of hurricane passage within 50 km of a sample of coastal locations. Probabilities are provided for the long-term average (1948-2022) and 2025 forecasts for Category 1 and higher and Category 3 and higher hurricanes. For the forecasts, uncertainty ranges are also provided at the 5% and 95% confidence level; that is, there’s a 5% chance the true value falls below the lower estimate (5%) or above the upper estimate (95%). The total number of hurricanes and major hurricanes that form in the season is also forecast to be elevated, though not as elevated as the local impact probabilities. The best-estimate forecast is 8.1 hurricanes (4 to 13, 5%-95% uncertainty) and 3.5 major hurricanes (1 to 7, 5%-95% uncertainty), compared to 1948-2022 mean values of 6.6 and 2.6. The uncertainty distribution is wide, and the distribution overlaps the 1948-2022 means. The smaller increase in total storm count compared to local probabilities highlights the importance of forecasting local impacts, not just Atlantic-wide formation rates. A small fractional increase in overall formation rate can lead to a larger increase in local probability. If a tropical cyclone reaches hurricane or major hurricane status even briefly during its life cycle, it counts as a storm formed at that intensity level. But by itself, the overall formation says nothing about how long the tropical cyclone remained at that intensity. Our model also predicts how long tropical cyclones remain intense. The combination of more hurricanes and major hurricanes and longer duration at those intensities increases the odds of a locality being impacted beyond merely the overall formation rate. In addition, the model predicts seasonal changes in average paths of tropical cyclones, which can have a further impact on local probabilities. The factors driving our hurricane forecasts are forecasts of the state of El Niño/La Niña, an irregularly varying signal in sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the tropical Pacific, and SST in the subtropical North Atlantic. We make use of SST forecasts from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), which has one of the best track records. As of early March, ECMWF forecast El Niño/La Niña states near neutral for June-July-August (the bulk of the hurricane season), but SST in the subtropical Atlantic significantly elevated above long-term averages. El Niño suppresses Atlantic hurricane activity, while La Niña enhances it, so a near-neutral forecast has little impact. Meanwhile, warm subtropical Atlantic SSTs drive active hurricane seasons. Taken together, the El Niño/La Niña and Atlantic SST inputs, when run through our model, result in elevated hurricane activity. Looking back: Analysis of our 2024 forecast Our successful forecast of the 2024 hurricane season lends credibility to the 2025 forecast. In March 2024 we forecast an upcoming season of highly elevated activity, driven by forecasts for a strong La Niña phase of El Niño/La Niña (Atlantic hurricanes tend to be more active during the La Niña phase) and extremely warm SSTs in the subtropical North Atlantic. While the 2024 La Niña was not as pronounced as ECMWF forecast, an extremely warm North Atlantic did occur, and the hurricane season was one of the most active on record. In March 2024, we forecast a 2024 formation rate of 14 hurricanes, with eight of them reaching major hurricanes status. The season actually experienced 11 hurricanes, including five classified as major. How good is this agreement? Seasonal forecasts are probabilistic in nature. That is, the best we can do is forecast a range of results. As seen in Figure 4, the 2024 forecast range is far more consistent with the actual numbers that occurred than is the long-term average distribution. In other words, the forecast performed better than just using historical average rates. Figure 5: Forecast impact probability maps for the 2024 season made in March 2024. Hurricanes of all intensities (Category 1 or higher) are shown on the left, while major hurricanes (Category 3 or higher) are shown right. Also shown (black dots) are observed locations of tropical cyclones when they were at hurricane and major hurricane intensity. The inset values are the Brier Skill Score (BSS) measures of the forecast performance, with positive values indicating skill. Looking beyond Atlantic-wide rates, we can also assess the performance of our forecast on a regional level. Figure 5 shows the forecast probability maps, and the observed hurricane tracks for all hurricanes and major hurricanes. Seasonal forecasts are inherently probabilistic — the maps display the probability of occurrence, not a deterministic forecast for a particular event at a particular time — and assessing the performance of the forecast requires the use of a probabilistic skill score diagnostic. In assessing the skill of such a forecast, one asks if the forecast assigned higher probability to what ultimately occurred than did long-term climatological average maps. A common probabilistic forecast diagnostic is the Brier Skill Score (BSS). The differences between the forecast probabilities and the ultimate occurrences (yes or no, 1 or 0) are summed up over the region shown in the maps. This sum is then repeated using the long-term (1948-2022) climatological probabilities instead of the forecast, and the two sums are compared. The BSS is designed so that BSS=1 is a perfect deterministic forecast (forecast probability of 1 where events occurred and 0 where they didn’t); BSS=0 indicates a forecast no better than long-term climatology, that is, no skill; and BSS<0 indicates a misleading forecast worse than climatology. A perfect BSS=1 is impossible to achieve, even for tomorrow’s weather forecast. But a useful forecast must have BSS>0. Our 2024 forecasts have BSS>0, indicating skill beyond climatology. For hurricanes of any intensity, the forecast’s BSS=0.12, and for major hurricanes BSS=0.07. As difficult and uncertain as seasonal forecasting is, this positive skill indicates that our forecast model has utility and lends credence to our 2025 forecast. The Atlantic is poised for another busy hurricane season in 2025. While not forecast to be as active as the 2024 season, nonetheless the probability of North American and Caribbean coastal regions being impacted will be significantly higher than the long-term average. Populations, businesses, and investors in these regions should pay close attention to hurricane forecasts and alerts as the season evolves. -

2025 Atlantic Hurricane Season

BarryStantonGBP replied to BarryStantonGBP's topic in Tropical Headquarters

“But increased trades” LMAO -

-

2025-2026 ENSO

michsnowfreak replied to 40/70 Benchmark's topic in Weather Forecasting and Discussion

Thanks to some good conversation with @Stormchaserchuck1 I dove further into the ENSO data for Detroit. And its actually surprising to see how relatively close the different ENSO states are, sensible weather wise. I suspect if many of you look at your local data, you may also be surprised. I think one of things is we all look into some of those "token" years and assume all ENSOs of that magnitude will yield similar results, but when you look at the mean...yes there are differences, but the differences are not as cut and dry as those cookie-cutter "what to expect this winter" graphics noaa puts out every fall before an expected El Nino or La Nina winter. Strong El Ninos here, as expected, are by far the warmest and least snowy...and weak La Ninas are the wettest/snowiest. But weak El Ninos are surprisingly the coldest and driest. Neutral are generally the preferred winters (and it doesnt show in this data, but 2nd and 3rd year neutral is usually REALLY the best). But all of that noise aside, all of the data is FAR closer than I was expecting. ALL El Ninos (27 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 27.9F DJF precip avg: 6.07” Season snow avg: 37.4” 1”+ snowcover avg: 44 days ALL La Ninas (25 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 27.8F DJF precip avg: 6.77” Season snow avg: 44.9” 1”+ snowcover avg: 49 days ALL Neutral years (23 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 26.6F DJF precip avg: 6.66” Season snow avg: 44.6” 1”+ snowcover avg: 55 days 1950-2025 AVG (75 years) DJF temp avg: 27.5F DJF precip avg: 6.40” Season snow avg: 41.5” 1”+ snowcover avg: 49 days DIFFERENT EL NINO STRENGTHS Strong El Ninos (9 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 30.7F DJF precip avg: 6.44” Season snow avg: 29.9” 1”+ snowcover avg: 31 days Moderate El Ninos (7 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 27.6F DJF precip avg: 6.29” Season snow avg: 42.3” 1”+ snowcover avg: 45 days Weak El Ninos (11 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 25.8F DJF precip avg: 5.63” Season snow avg: 40.4” 1”+ snowcover avg: 55 days DIFFERENT LA NINA STRENGTHS Strong La Ninas (7 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 27.7F DJF precip avg: 6.72” Season snow avg: 49.2” 1”+ snowcover avg: 53 days Moderate La Ninas (6 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 28.0F DJF precip avg: 5.46” Season snow avg: 37.7” 1”+ snowcover avg: 40 days Weak La Ninas (12 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 27.8F DJF precip avg: 7.45” Season snow avg: 46.0” 1”+ snowcover avg: 51 days -

2025 Atlantic Hurricane Season

BarryStantonGBP replied to BarryStantonGBP's topic in Tropical Headquarters

You’re welcome im mostly ignoring any howling for “below normal or normal” seasons because they’re only focusing on “but the MDR IS COLD” they have been hyper fixating on Eastern Africa and yes it will reheat in the coming weeks as trades lessen. I don’t know why they’re jumping to conclusions plus models can be incorrect sometimes if you remember 2018-19 and of course 2022 I have just checked the Caribbean and gulf ssts still above normal even the ohc so I don’t know why they’re jumping to conclusions plus I look at the LRC and more for landfall risks I am looking at an above average season despite howling yourself? -

You remembered! Yes, I work in vector disease ecology, and we monitor the downstate region for ticks, mosquitoes, and all the diseases they bring us. So far, it is too early to tell if this is a high year for ticks or not when speaking about numbers. It is off to an early start, though. However, if it stays dry with low humidity, that will absolutely stress the tick population. Based on the relatively cold and dry winter, though, we would forecast an average to below-average tick year. As for mosquitoes, too bad we can’t get a late low 20s freeze overnight this week to decrease their numbers. If it stays dry, though, they may have similar issues. I don’t think we will stay dry, though, unfortunately. I think the humidity and thus moisture will pick up by June.

-

For reference if youd like to look up your areas data: Strong Ninos: 1957-58, 1965-66, 1972-73, 1982-83, 1987-88, 1991-92, 1997-98, 2015-16, 2023-24 Moderate Ninos: 1951-52, 1963-64, 1968-69, 1986-87, 1994-95, 2002-03, 2009-10 Weak Ninos: 1952-53, 1953-54, 1958-59, 1969-70, 1976-77, 1977-78, 1979-80, 2004-05, 2006-07, 2014-15, 2018-19 Strong Ninas: 1973-74, 1975-76, 1988-89, 1998-99, 1999-00, 2007-08, 2010-11 Moderate Ninas: 1955-56, 1970-71, 1995-96, 2011-12, 2020-21, 2021-22 Weak Ninas: 1954-55, 1964-65, 1971-72, 1974-75, 1983-84, 1984-85, 2000-01, 2005-06, 2008-09, 2016-17, 2017-18, 2022-23 Neutral: 1950-51, 1956-57, 1959-60, 1960-61, 1961-62, 1962-63, 1966-67, 1967-68, 1978-79, 1980-81, 1981-82, 1985-86, 1989-90, 1990-91, 1992-93, 1993-94, 1996-97, 2001-02, 2003-04, 2012-13, 2013-14, 2019-20, 2024-25

-

Its quite gusty here.

-

For the past several years Ive been reading the ENSO threads in the main weather forum. Usually some good discussion. Different regions prefer different ENSO states. But I decided to actually really dive into the date (for Detroit) because it was pointed out that its not always as cut and dry as it seems. I analyzed the winters since 1950 (which is when the main enso chart starts). We all have seen those cookie-cutter "what to expect this winter" graphics they put out every year for El Nino or La Nina. But with enso being just ONE piece of the puzzle, its really not as simple as that. I always knew that, but to see how close actual data was was shocking. IN SUMMARY- By far, STRONG El Ninos are the worst, as expected. They are by far the warmest and least snowy. But not really that dry - near normal precip in fact. The driest enso state is them all is a WEAK El Nino - but thats also the coldest and with the most snowcover. Colder than any La Nina or even neurtral! The wettest and snowiest state is a WEAK La Nina. There are definitely differences, but the differences are far smaller than I anticipated. THE DATA: When you break down simply as El Nino, La Nina, or Neutral, the data is remarkably close. ALL El Ninos (27 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 27.9F DJF precip avg: 6.07” Season snow avg: 37.4” 1”+ snowcover avg: 44 days ALL La Ninas (25 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 27.8F DJF precip avg: 6.77” Season snow avg: 44.9” 1”+ snowcover avg: 49 days ALL Neutral years (23 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 26.6F DJF precip avg: 6.66” Season snow avg: 44.6” 1”+ snowcover avg: 55 days 1950-2025 AVG (75 years) DJF temp avg: 27.5F DJF precip avg: 6.40” Season snow avg: 41.5” 1”+ snowcover avg: 49 days DIFFERENT EL NINO STRENGTHS Strong El Ninos (9 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 30.7F DJF precip avg: 6.44” Season snow avg: 29.9” 1”+ snowcover avg: 31 days Moderate El Ninos (7 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 27.6F DJF precip avg: 6.29” Season snow avg: 42.3” 1”+ snowcover avg: 45 days Weak El Ninos (11 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 25.8F DJF precip avg: 5.63” Season snow avg: 40.4” 1”+ snowcover avg: 55 days DIFFERENT LA NINA STRENGTHS Strong La Ninas (7 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 27.7F DJF precip avg: 6.72” Season snow avg: 49.2” 1”+ snowcover avg: 53 days Moderate La Ninas (6 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 28.0F DJF precip avg: 5.46” Season snow avg: 37.7” 1”+ snowcover avg: 40 days Weak La Ninas (12 since 1950) DJF temp avg: 27.8F DJF precip avg: 7.45” Season snow avg: 46.0” 1”+ snowcover avg: 51 days

-

Wind?

-

This wind is annoying...I don't want to locate inside though ughhhh

-

Training sleepy rumblers this morning as the main action, if any, moves off to the ESE. I hope this boundary sets up south of I70 so I'm on the cool side and can stay out of a couple of days of rain trains. We've had so much rain the grass is trying out for the NBA

-

36F to 71F currently.

-

Fast tracking Net Zero

-

Low of 41F. Could be a 40-degree day here.

- Today

-

Similar story in many spots, with unprecedented morning temperatures.